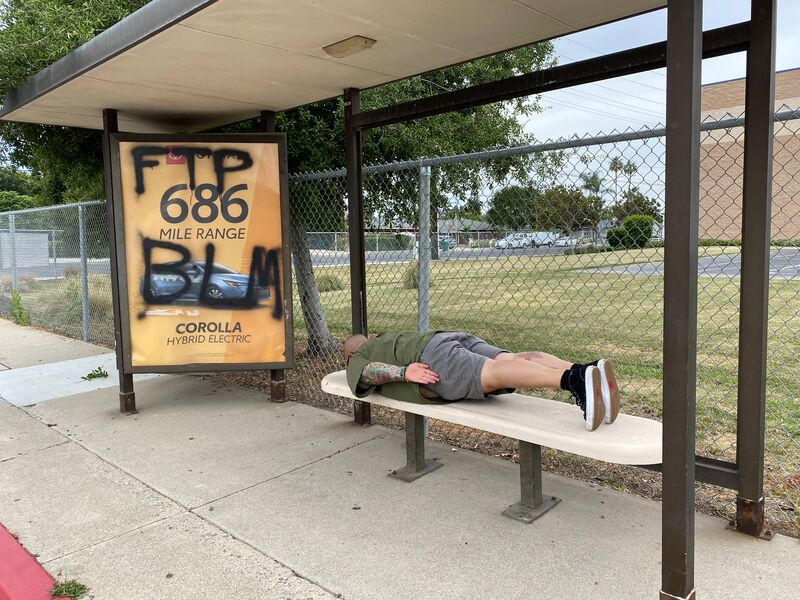

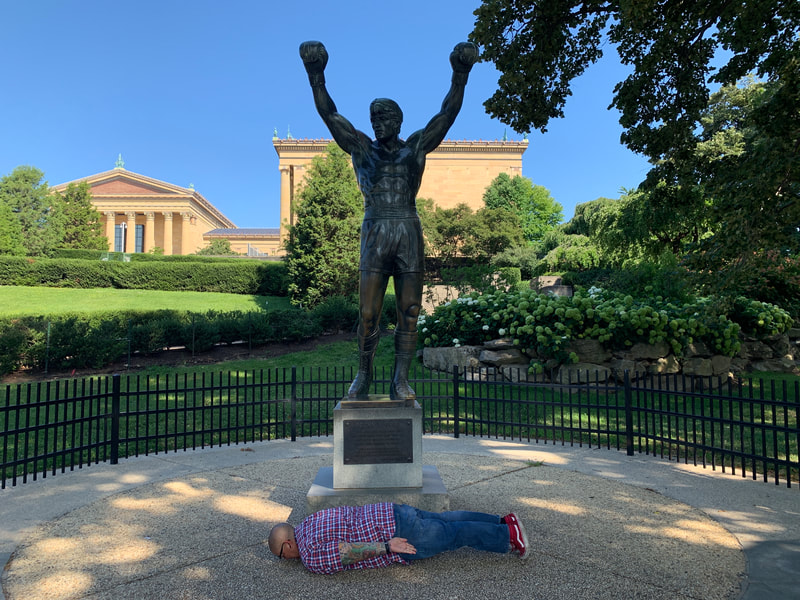

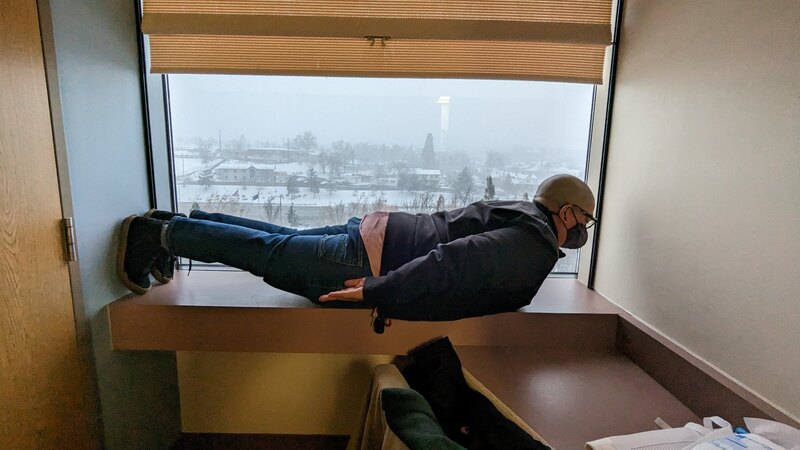

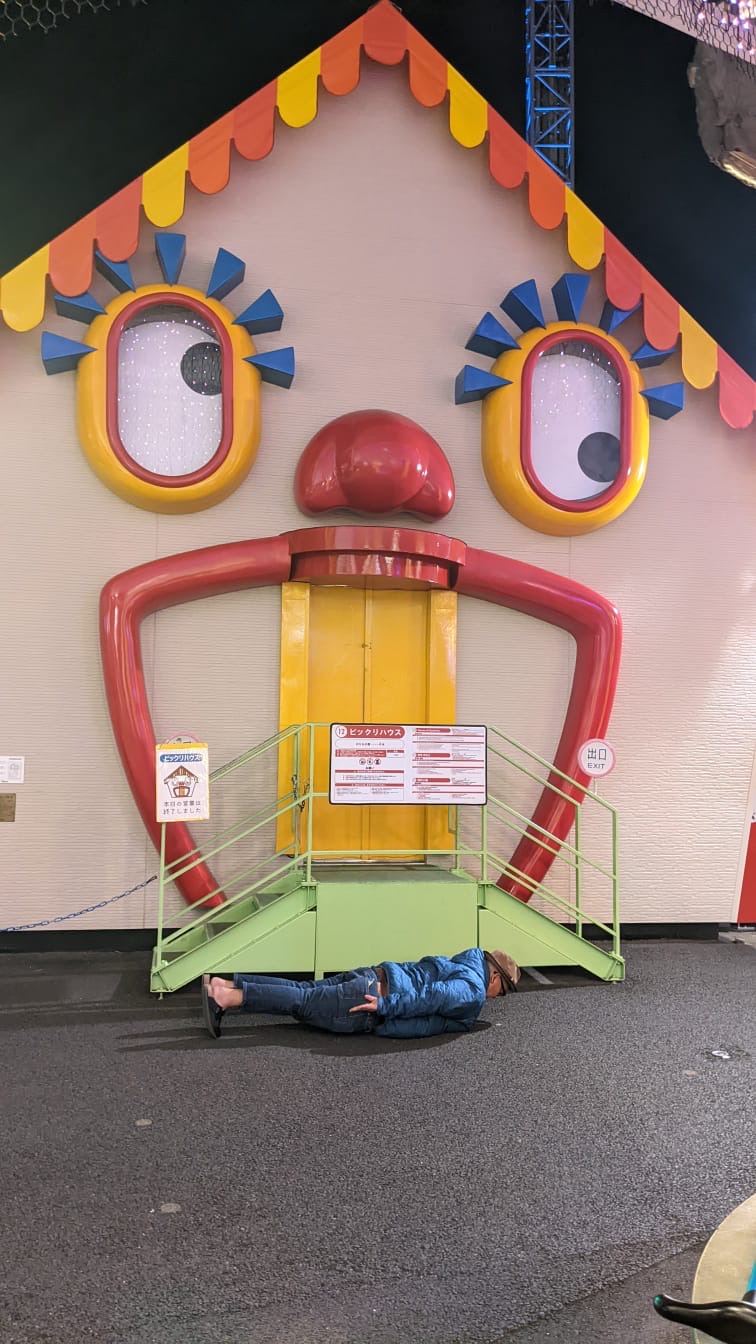

PLanks a lot

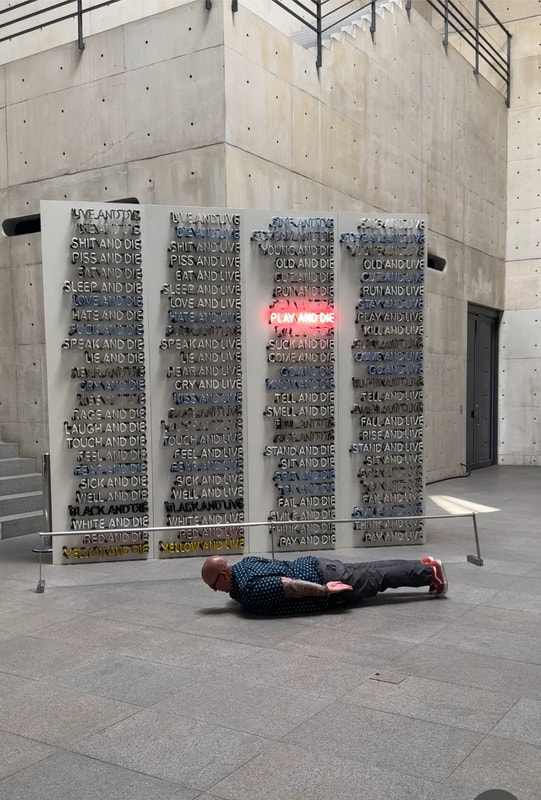

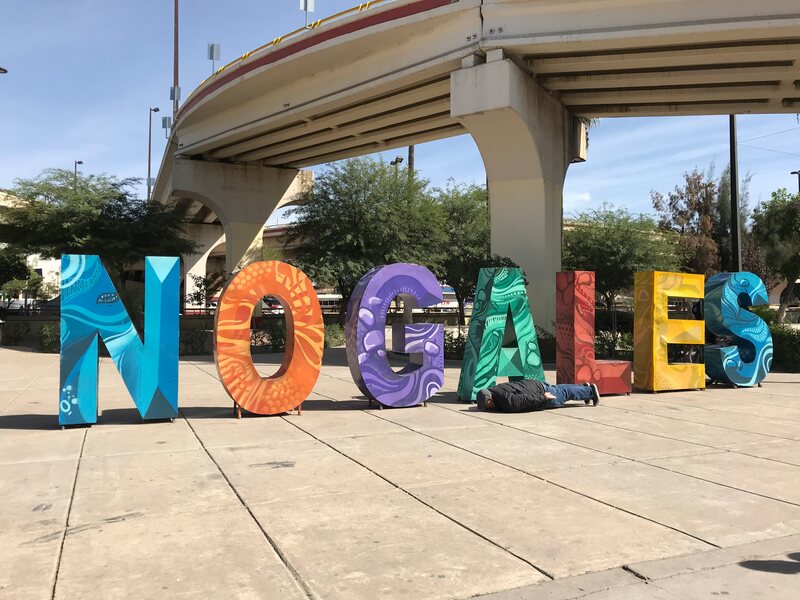

"Planking is an activity consisting of lying in a face down position, sometimes in an unusual or incongruous location. The palms of the hands are typically touching the sides of the body and the toes are typically touching the ground. Some players compete to find the most unusual and original location in which to play. The term planking refers to mimicking a wooden plank. Planking can include lying flat on a flat surface, or holding the body flat while it is supported in only some regions, with other parts of the body suspended. Many participants in planking have photographed the activity in unusual locations and have shared such pictures through social media."

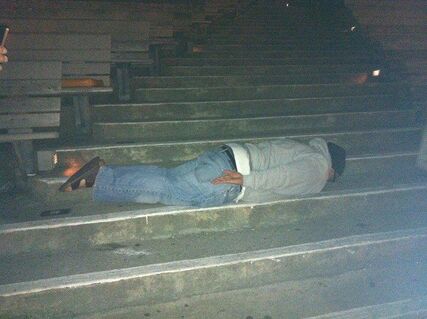

While the "planking fad" became popular in 2011, my first plank was in 2012 at the Hollywood Bowl (Los Angeles, CA) and I have never stopped since.

It would seem I plank as much as I sit in a chemo chair for infusions. So it's the "yin" to my "yang" and my response to wanting to live each day to the fullest.

It would seem I plank as much as I sit in a chemo chair for infusions. So it's the "yin" to my "yang" and my response to wanting to live each day to the fullest.